Street Aesthetic is NOT Street Photography

The many names of street aesthetic, urban theory and the blurred line between documentary & street photography.

Over the past 16 years, I have spent a lot of time dedicated to learning about street photography. I’ve noticed a trend, one that makes me a bit concerned regarding the future of the genre as we’ve been conditioned by social media to create and share an approved version, photos that sensationalize and/or romanticize rather than focus on everyday life. More specifically, street aesthetic being pushed as street photography. Street photography is not a style but a genre, and describing it as an aesthetic alters the genre to focus on the physical rather than the content and story of the moment. With a perceptive eye, I can say that this shift in how street photographers are sharing this work is about marketing and branding rather than artistry.

To understand what the difference is, we have to define each term. “The term ‘aesthetic’ has come to designate, among other things, a kind of object, a kind of judgment, a kind of attitude, a kind of experience, and a kind of value.”1 This definition is broad but is mostly understood as a vibe that is evoked through appearance/style. In regards to history, “the aesthetic movement was a late nineteenth century movement that championed pure beauty and ‘art for art’s sake’ emphasizing the visual and sensual qualities of art and design over practical, moral or narrative considerations.”2 Today, aesthetic is a term used to fit into a subcategory related to a trend, examples including academia, grunge, croquette, edgy, cottage-core, urbanism, etc. As described by author Gretchen McCollough, “when you talk about someone having an aesthetic or that is or isn't ‘my aesthetic’ then you're getting your metaphor from the world of art.”3

Although photography may be described as an artistic medium, the act of taking photos is not about creating a moment but documenting a person, place or interaction, and the artistry relates to how photos are edited and presented. Street photography is a genre that focuses on photographing life in public, “the very publicness of the setting enables the photographer to take candid pictures of strangers, often without their knowledge.”4 There is an expectation that photos are spontaneous and there is little to no interaction/acknowledgement by the subject photographed, but this is not always the case. One of the first people credited with documenting everyday life was Charles Nègre, who used his camera to document architecture as well as shops, laborers, traveling musicians, peddlers, and “unusual” street types in the 1850s. Today, many photographers interested in the genre often reference Henri Cartier-Bresson, noted for coining the term the decisive moment, who discussed “capturing an event that is ephemeral and spontaneous, where the image represents the essence of the event itself.5” This term is often associated with photojournalism and documentary photography, although it is considered for street photography, as well.

Based on the criteria of each term’s definitions, street photography is a genre that is related to documentary photography and the equivalent of urbancore, an aesthetic that is also known as metropolitan, streetcore, citycore, and urbex. The urbancore aesthetic focuses heavily on city life which is related to the Urbanism theory, discussed in sociology and related to the development of cities and how city planning and locations (buildings, businesses, parks, man-made structures) influence human behavior. “Urbanism can be understood as placemaking and the creation of place identity at a citywide level… as early as 1938, Louis Wirth wrote that it is necessary to stop 'identify[ing] urbanism with the physical entity of the city', go 'beyond an arbitrary boundary line' and consider how 'technological developments in transportation and communication have enormously extended the urban mode of living beyond the confines of the city itself.'6" In other words, urbanism changed from a theory to an aesthetic as it referenced the flow and energy of life in developed places, essentially any place that experiences developments such as the construction of roads with gas stations, motels/hotels, shops, etc. Today, when referenced with photography, urbancore is associated with street fashion and elements like graffiti, industrial architecture (rooftops, alleyways, train stations, older/empty buildings, skyscrapers), street fixtures (street lamps and road signs), subways and bridges, warehouses and items such as dumpsters and concrete.

Urbancore is street aesthetic, as it relates to the physical elements of a place and the environment’s influence on those who exists in that area, and this can be experienced anywhere man-made infrastructure is built. Street photography is the genre of documenting everyday behaviors in public spaces, often associated with life in cities as many photographers live in this environment. However, the definition implies that these photos showcase the everyday, not only life in cities, meaning a photographer can chose to document their everyday experiences and/or photograph the experiences of others with/without an urban setting. The street aesthetic work that is being pushed by algorithms, often tagged as street photography, is over-saturating these platforms due to the universal appeal of the term, the constant trending due to its overuse rather than the accuracy of the tag itself. My theory is that many photographers are not aware of the differences as social media has discouraged education and reduced photography to be consumed as content. A recent video, “POV Street Photography is Ruining The Genre,7” discusses the phenomenon of POV street photography videos, and how photographers have been inspired to share first-person footage of their outings with clips showing their exploration of their city/town and “behind the scenes” footage showing their perspective as they take photos, this trend drastically increasing since 2020.

2020 was a chaotic year. Most were not heading out in the first half of the year due to restrictions, but it was a turning point for many who discovered/rediscovered street photography due to having more free time and embracing hobbies to be productive or to stay sane. Many became interested in street photography due to watching content on social media, inspired by photographers sharing archive work and discussing gear, books and photos that inspired them. With more people online at this time, the algorithms on various platforms such as Instagram, TikTok and YouTube began to push video content over photos, rewarding highly engaged posts with more reach. Many content creators were sharing clips of their outings, with social distancing allowing “amateur” (I hate this word, but it is accurate) photographers to invest in zoom lens and photographing from a distance, documenting subjects from further away.

This provided photographers with the opportunity to “dip their toes” into taking street photos, often focusing on elements of city life rather than the people there with the exception of individuals walking past as the camera captured the moment from a safe distance. One photographer who goes by the handle poetic.duck (name is Ted J), featured in the POV video has photos from 2020 that showcase street aesthetic. The photo that caught my attention is a black & white image of two people walking down a street, their faces unseen and covered by an umbrella, photographed walking downhill with an overview of the street and the neighborhood past them. This photo is about the city environment rather than their life in that city as the people who are photographed are not being documented to showcase their everyday experience but a romanticized moment of a rainy day; as the viewer, the position and angle of the camera allows the street, glistening from rainfall, to illuminate and isolate the people walking, the parallel rows of buildings and accompanying street fixtures such as electricity poles and lines, awnings, cars, and the overview of the neighborhood ahead of the duo emphasizes the scale and location rather than photographing an everyday/candid experience. In a way, the people are like mannequins, seen posing in the distance and lack distinguishable features.

Some may counter that a street photo doesn’t necessarily have to have people in it which is true. However, if a location and/or item doesn’t allude to the life of a person/community and its importance in everyday life, this can be described as a documentary photo or a still life. For example, a subject I associate with cities but can be found in other locations such as green areas are pigeons, which were domesticated to be carriers and pets but now many freely wander and fly in flocks. The photo (below) contains all the elements of urbancore: graffiti on the wall in the left half of the frame, a power line dangling from the top left of the building and down past a “NO STANDING fire zone” sign, cascading past bricks painted white, residue dripping from a pipe protruding in the upper right half of the wall, and a row of pigeons standing on the rooftop with one flying over the sign. The viewer sees elements associated with urban development, but there isn’t anything to distinguish where this was photographed and the community itself. From the context provided by the photographer, this photo was the first of a set documenting pigeons in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Many could/would consider this a classic street photo due to the timeless/romanticized subject of pigeons, but it is most definitely categorized as street aesthetic and documentary due to the notes regarding the date and boroughs.

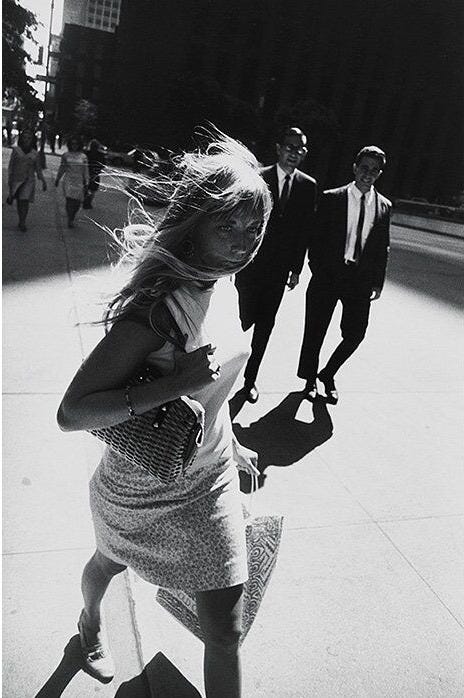

Lastly, portraits may be considered street aesthetic if they focus on street fashion (makeup, clothing, accessories and hairstyle) of a person photographed rather than someone passing by. Specifically, two examples which come to mind that embody street aesthetic and street photography are the following:

The first photo has elements related to urbancore, specifically street fashion that reflects trends associated with youth today. However, the viewer is not able to identify where this was photographed. In the description of the photo, Máximo mentions the names of the subjects, suggesting that he may know them and hints that the moment may have been captured while engaged in conversation. The actions are subtle and the interaction between Declan and Maximus, the cat, showcase their bond, and the pins and headphones worn by the subjects also hint at the interests of the people photographed. In comparison, the black and white photograph taken by Garry Winogrand documents a woman heading towards him with two men in suits walking behind her (to her left, the viewer’s right), with sunlight creating a bubble of light around them, cascading across the sidewalk. Her face, although partially covered by strands of her hair, is fully visible, her eyes looking past the photographer, her body angled as she walked past. The men behind her are visible except for the right arm of the man on the left. Although the year isn’t noted, the styles of their outfits could be worn today, ensembles that could blend in effortlessly, but reflect the past as Garry Winogrand passed away in 1984. Both photos have a classic feel, the lack of technology (smart phones, tablets, electronic signs, etc.) and the clothing and accessories evoke nostalgia. The main difference is that one photographer lists who is photographed and the other didn’t. This doesn’t mean that the photo taken by Winogrand was candid, simply that we have not been provided the context to determine if it was a spontaneous moment.

To conclude, a street photo can have elements of the street aesthetic but it has to focus on the action/reaction rather than the “vibes,” and street aesthetic will focus on the energy and style rather than how those aspects impact everyday life. Many may consider these differences to be insignificant, however it can be debated that every element is important to the strength of a photo, including how we discuss and present work. The lack of critical discussion regarding the genre deliberately facilitated by content creators who mention street photography for clickbait has led to labelling any and every moment outside our homes (or taking place in a man-made location) that is spontaneous as street photography, which is simply not the true of every photo. I can’t help but wonder if many would even take and share street photos if social media wasn’t available. Lastly, this is not an essay to discourage photography enthusiasts from taking photos because it overwhelms them to associate work to the “correct” genre, but to encourage critical analysis of the photos we view, share and discuss. Above all, we should embrace curiosity and take delight in studying photos that intrigue us.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aesthetic-concept/

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/aesthetic-movement

https://www.vogue.com/article/do-i-have-an-aesthetic

https://www.britannica.com/art/street-photography

https://neomodern.medium.com/revisiting-the-decisive-moment-8c71efcabb72

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urbanism

Interesting piece! I think what is actually in the frame is of far greater importance than genre names and categories though, and a greater critical consideration. There are way too many “street” photographs, in whatever sub-genre they might belong, that see composition and balance in the frame as an unnecessary concern.

As always. Incredibly insightful writing Dani.